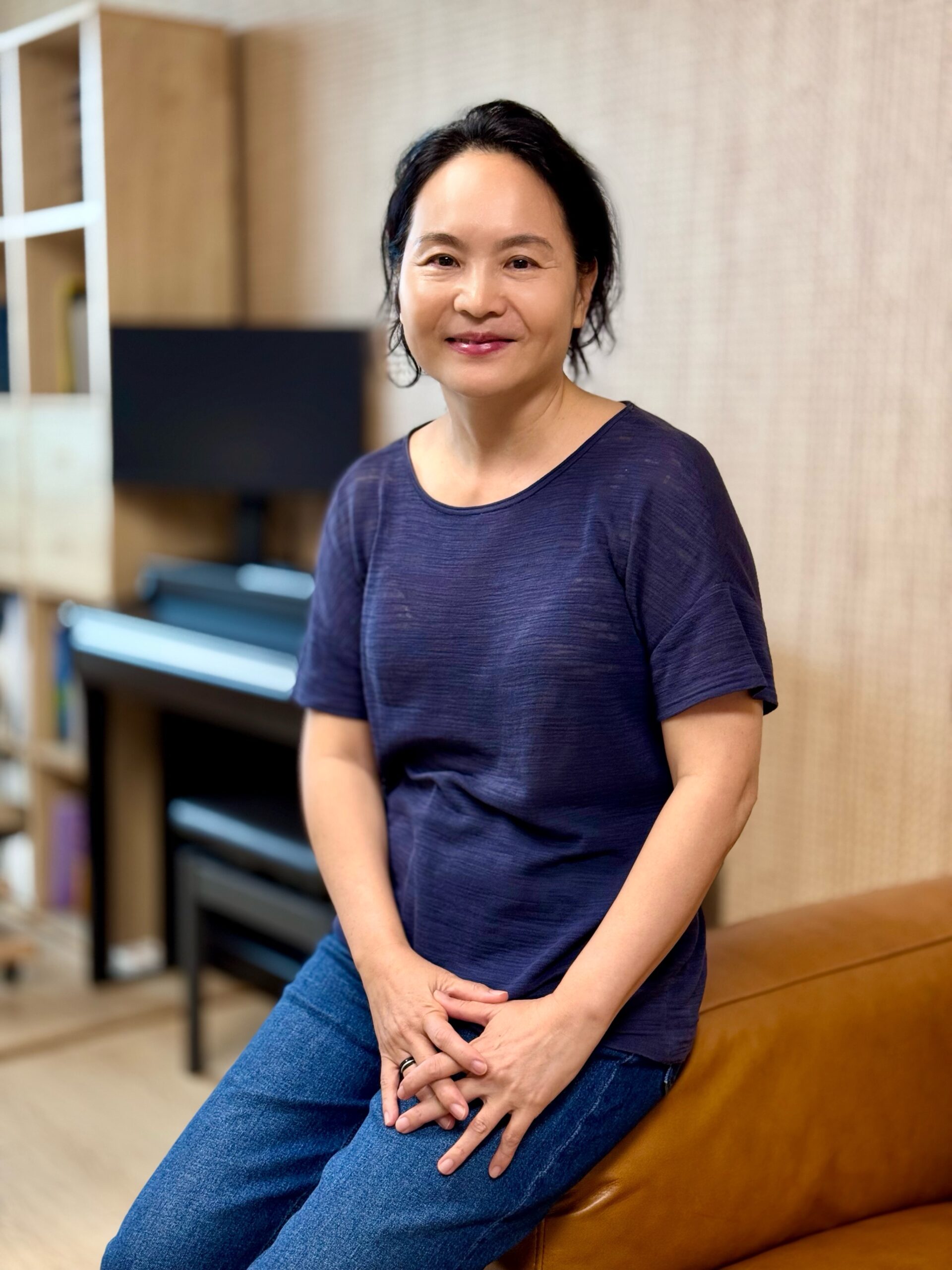

We had the rare privilege of meeting renowned film composer Shim Hyun-jung at her studio in Hongdae (Seoul, South Korea), between two concerts, in the midst of an eight-concert retrospective series held in Busan, running through late November.

If her name does not immediately ring a bell, chances are her music does: remember The Last Waltz from Oldboy (올드보이), directed by Park Chan-wook — a film for which she composed the majority of the score under the supervision of Jo Yeong-wook. (If you haven’t yet had the opportunity to see it, Oldboy remains widely available and has been beautifully restored and remastered for its 20th anniversary.)

In our conversation, Shim Hyun-Jung looks back on her youth and retraces a journey marked by obstacles and resilience, leading to the launch of her career — even though the challenges were far from over as a woman film composer navigating a traditionally male-dominated industry. Her determination, artistic integrity, and remarkably prolific career left us as impressed as we were inspired.

Oldboy is a South Korean film directed by Park Chan-wook, released in 2003. Widely acclaimed, it received numerous awards, including the Grand Prix du Jury at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004, and was also honored for its music at the 2004 Korean Film Awards (MBC).

Part of Park Chan-wook’s Vengeance Trilogy, Oldboy is the second installment, following Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and preceding Lady Vengeance (2005).

« I grew up in a fairly ordinary family and played the piano as a hobby. When the Catholic church I used to attend was rebuilt, a pipe organ, a rare instrument at the time, was donated to the church. They needed an organist to serve during Mass, and I volunteered to be trained.

Learning the pipe organ felt like discovering a small orchestra, with so many different and beautiful instruments combined into one. While playing Bach’s organ works, I just fell in love with music. By the age of sixteen, I knew I wanted to become a professional musician.

In order to study the pipe organ at university, I was required to audition on the piano rather than on the organ. I therefore took intensive piano lessons with an piano expert. Despite starting piano training professionally at a relatively late age, I practiced relentlessly. However, after auditioning me, my music teacher did not encourage me to pursue organ studies, as my piano skills were not yet sufficient.

I spent days sitting at the piano in tears, and it was during that time that I truly realized how deeply I wanted to become a musician. One day, a friend of my older brother, who was studying at a music school, suggested that I apply for a composition major, noting my perfect pitch and strong sight-reading abilities. At first, I wondered what a female composer could possibly do—I had never seen one myself.

As I began taking lessons with him, I discovered that composing music was exciting. Studying composition professionally at university proved both challenging and demanding, but also exhilarating. At my graduate recital, despite the intense preparation involved—both in composing the works and rehearsing with the musicians—some old friends in the audience told me that my music was difficult to understand. This was hardly surprising: the pieces were atonal, based largely on whole-tone scales, a musical language unfamiliar to most listeners.

It was at that moment that I decided I wanted to create music that could truly communicate with people.

America

After backpacking across Europe for about a month, I traveled to the United States to further explore Western music. I first went to Nebraska, where my childhood next-door neighbor lived, with the intention of studying the language before applying for graduate studies a few months later. However, not obtaining the required language score in time meant that I had to stay an additional year and apply the following cycle.

During that time, I went through experiences I had never encountered before in my life: witnessing the death of a college student in a swimming pool, working as a waitress in a Korean restaurant, and being abandoned by people I trusted. At the same time, making friends from different countries and studying at a music school for one semester meant a great deal to me.

Through my professor, I discovered contemporary minimalist music by composers such as Terry Riley, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich. It felt like entering a new world and greatly expanded my perspective on classical music.

Later, moving to New York to pursue a graduate program further broadened my understanding of the world through diversity. My composition teacher there, Ken Walicki, a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen, introduced me to music technology and computer-based composition, and guided me in finding my own artistic voice.

Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, having been called the « father of electronic music », for introducing controlled chance (aleatory techniques) into serial composition, and for musical spatialization.

New York

The program offered a strong focus on film studies and included a dedicated film music class. As part of that course, I composed music for a short video clip as an assignment, which received positive feedback from both the instructor and my classmates. This experience led me to discover my aptitude for film music.

Studying and living in New York—full of surprises and constant stimulation—broadened my horizons and helped me mature as I navigated both financial and academic challenges.

While composing music for a short film by a Korean film student, I was contacted by director Lee Myung-se, who had come to New York after completing Nowhere to Hide (1999). He invited me to compose the music for his friend’s dance performance directed by him.

This collaboration proved to be a pivotal opportunity and led to my introduction to Jo Seong-wu, a key figure in the Korean film music industry. Despite spending several months as an intern at the studio of five-time Emmy Award–winning composer Jamie Lawrence, I ultimately decided to return to Korea.

Nldr : to clarify — Jo Seong-wu ran a film music studio, while Jo Yeong-wook was a music supervisor.

Korea

In order to find work in my home country, I first had to understand the professional culture of the field. People do not readily speak openly about personal matters, yet film crews must bond quickly and work in close collaboration to ensure efficiency. Social drinking plays a role in fostering that sense of closeness. I tried to enjoy this practice and it became a way to connect with directors from other generations and secure projects.

At Jo Seong-wu’s Studio, film students collaborated with assistant composers like myself, allowing me to gradually build my career. Several of the short films I worked on were selected for international festivals, including Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival and Leeds International Film Festival.

At the same time, I was teaching Digital Music at a university. A screenwriting professor there later introduced me to Jo Yeong-wook, who would go on to become the music supervisor for Oldboy, as he was then looking for composers.

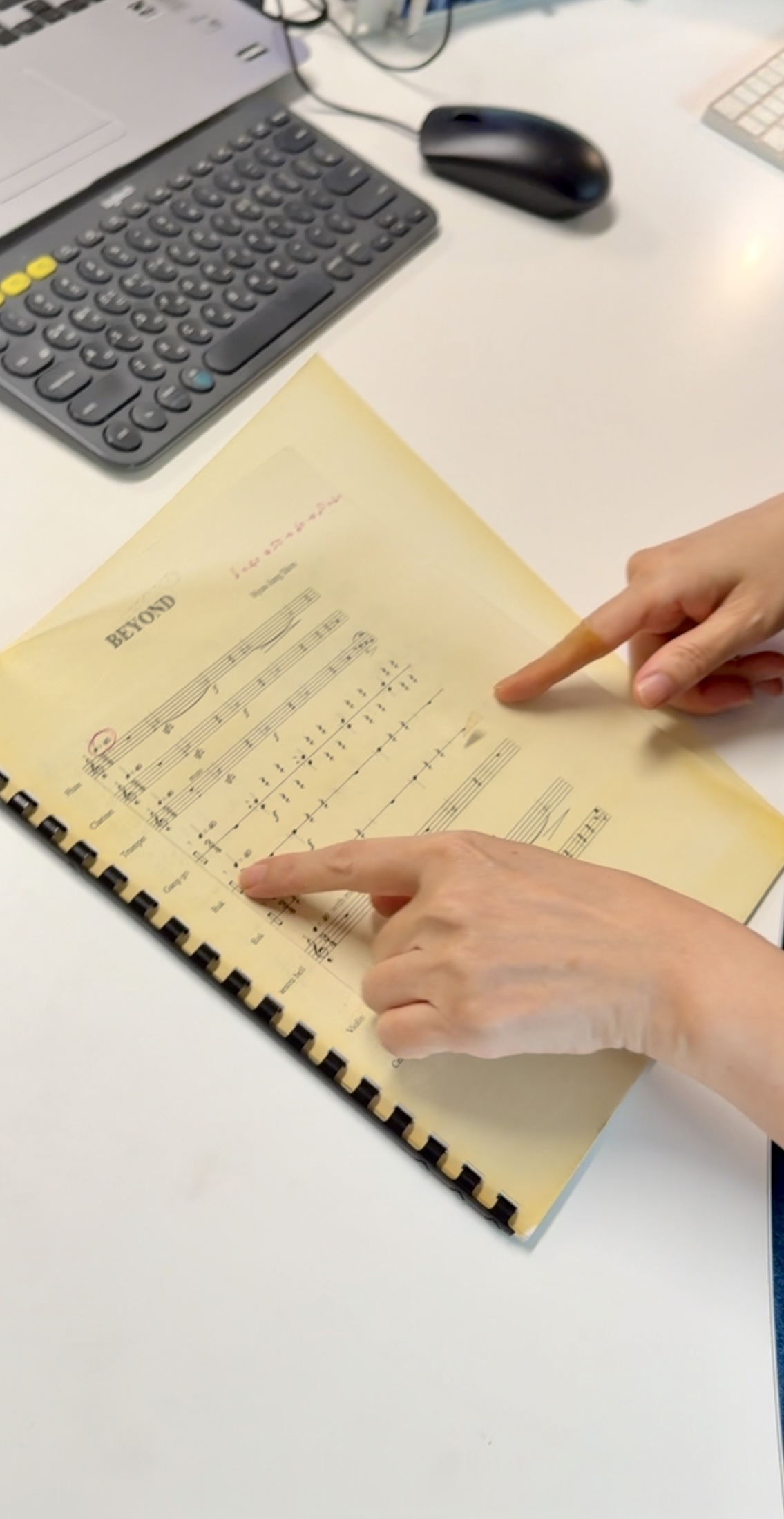

Jo Yeong-wook then invited me to work on a major project, which required both original compositions and arrangements of classical pieces. Following this collaboration, he asked me to join his next film, Oldboy.

After reading the script, I was overwhelmed by emotion. It was dark, bitter, violent and sense of resentment resonated deeply with me, particularly as I was going through a difficult period in my personal life at the time. Those hardships shaped the music of Oldboy; without them, I would not have been able to fully understand the characters’ emotional states.

The film’s visual language felt stark and restrained, which led me to compose in a similarly minimalist style for the more mysterious scenes, drawing inspiration from composers such as Philip Glass. For the famous hammer scene, however, my musical inspiration came from Linkin Park, whose music I was deeply immersed in at the time.

A waltz theme runs through the film as well, associated primarily with the female character and returning in the final moments.”

The film’s success ultimately launched her career, which would go on to include numerous film scores featuring major actors, as well as acclaimed documentary soundtracks. Her work achieved significant recognition both in Korea and internationally, with notable successes such as The Man from Nowhere, directed by Lee Jeong-beom and released in 2010.

The Man from Nowhere (Ajeossi, 아저씨) is a South Korean crime thriller written and directed by Lee Jeong-beom, released in 2010 and starring Won Bin and Kim Sae-ron. The film earned Shim the Hyun-Jung Best Music Award at the 2010 Korean Film Awards and became the highest-grossing Korean film of the year, surpassing Inception by Christopher Nolan at the domestic box office.

When asked about her most meaningful memory, her answer is surprising — and yet, perhaps not so unexpected. Rather than a major Korean production, she cites a French film, Koan of Spring, by Marc-Olivier Louveau, as the project that left the deepest mark on her.

Today, Shim Hyun-jung continues her career actively, supervising numerous projects and still teaching. Yet when asked what she truly wishes to do next, her answer is clear: she would like to return to her roots — to compose freely again, to work on projects that genuinely resonate with her, and, ideally, to collaborate once more on European productions.

And we would be delighted to welcome her in Switzerland for a concert or a project, don’t you think so?